Business Continuity Planning for COVID-19 Coronavirus

On 24 February the Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern, said there was a very high chance COVID-19 will reach New Zealand. That has now happened with the first case in Auckland in a traveller just returned from Iran. We were fortunate as the person showed obvious symptoms of the disease, and his family did all the right things. It has also been fortunate that the disease has taken so long to get to New Zealand, giving us time to prepare from a business continuity perspective.

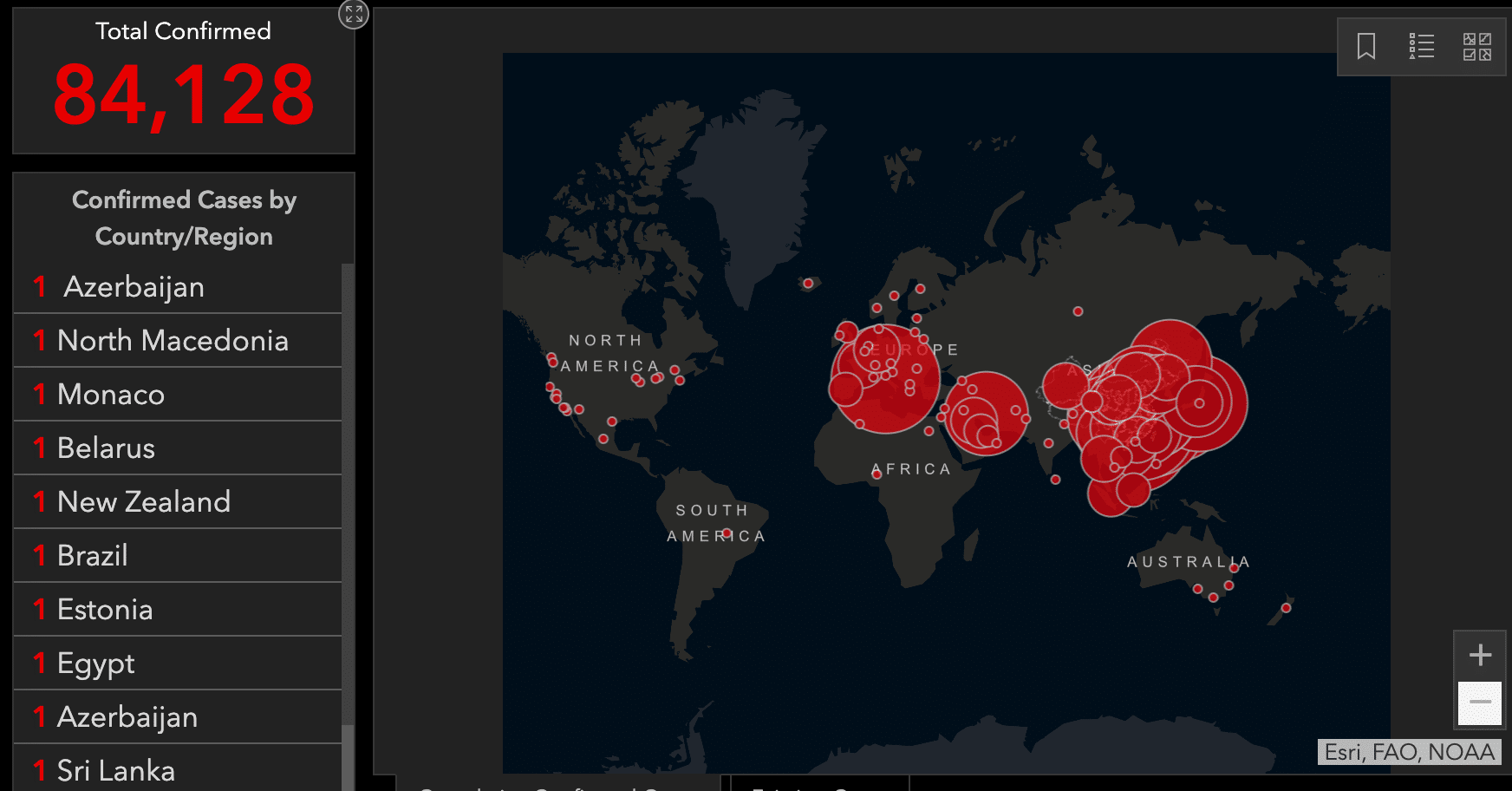

COVID-19 Pandemic – 29 February 2020

What should we be doing as business owners and managers to ensure business continuity?

The New Zealand government has issued a range of personal health advice. Relevant advice for businesses has been helpfully collated here by the Institute of Directors and here by the Ministry for Business Innovation and Employment.

It’s important to understand the context. The 2017 New Zealand Influenza Pandemic Action Plan, published by the Ministry of Health sets out how public health officials will manage an influenza epidemic in New Zealand, through a hierarchy of responses:

- Plan for it

- Keep it out

- Stamp it out

- Manage it

- Recovery

The COVID-19 coronavirus appears to be spreading strongly in Iran. That’s just a flight way from conflicts in the region where it could easily become endemic. And today California has reported its first case of local transmission with no apparent source. That is worrying officials as the case suggests that the disease is already embedded in the community. So it’s almost certain that the disease will spread within other countries.

None of the risk management professionals at workshop of risk management professionals convened by Risk NZ that I participated in earlier this week opined that an outbreak of COVID-19 wouldn’t happen in New Zealand.

It’s a matter of when, not if.

How should we prepare to ensure business continuity? In this blog I outline:

- a business continuity planning scenario for how a COVID-19 coronavirus epidemic in New Zealand might unfold, and

- a business continuity planning case study from our own specialist risk management consulting company.

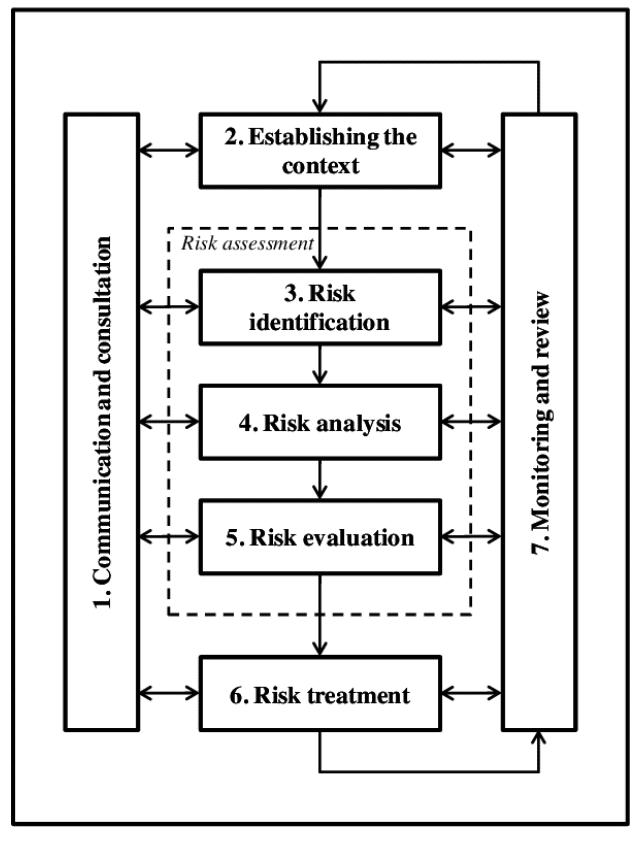

Applying a Risk Management Approach

In a companion post Geraint Bermingham comments on how business continuity planning for this epidemic can be considered under the 4Rs approach. We’ve also applied processes from the international standard ISO31000:2009 Risk Management to gain further insights. Fortunately the ISO risk management approach is simple to understand (Figure 1). In the following sections I go through some of the main steps.

Figure 1 ISO 31000:2009 Risk Management

Risk Management Framework – After ISO31000:2009

2. What’s the Context?

We’re a specialist risk management consulting business with the following key characteristics:

- operating from three locations: Auckland, Wellington and Queenstown

- normally all staff are office based, or at client meetings or in the field

- we travel frequently in New Zealand and more rarely overseas on assignments

- our work frequently requires meetings with up to 20 people.

The scenario that this plan is designed to address is circumstances when we can no longer work from our premises. The purpose of the plan is to allow the business to continue to operate in a changed context of a pandemic, while keeping safe our staff and people who we interface with.

A feature of our business is that we have no direct interactions with members of the general public. However many of our clients do and are implementing a range of measures to help keep staff safe.

3. What Could Happen? (Business Continuity Risk Identification)

Under the current pandemic threat the main risks to our business, going from the most immediate to the longer term are:

- Contagion: one or more of our staff falls ill and inadvertently spreads the virus in the workplace, or to people who we’re interfacing with

- Availability: some of our staff fall ill, are exposed to the virus, or otherwise can’t come to work due to changes in their domestic circumstances (e.g. school or childcare closed)

- Lockdown: compulsory lockdowns or adherence to voluntary health recommendations from health authorities prevents us from being able to access our workplaces

- Inputs: we can’t complete projects because we can’t get the required client or third party inputs

- Postponements: we can’t start projects because we can’t get the required approvals due to absences. Some projects are postponed or cancelled.

All of these events have knock-on effects through the business.

4. What could go wrong ? (Risk Analysis)

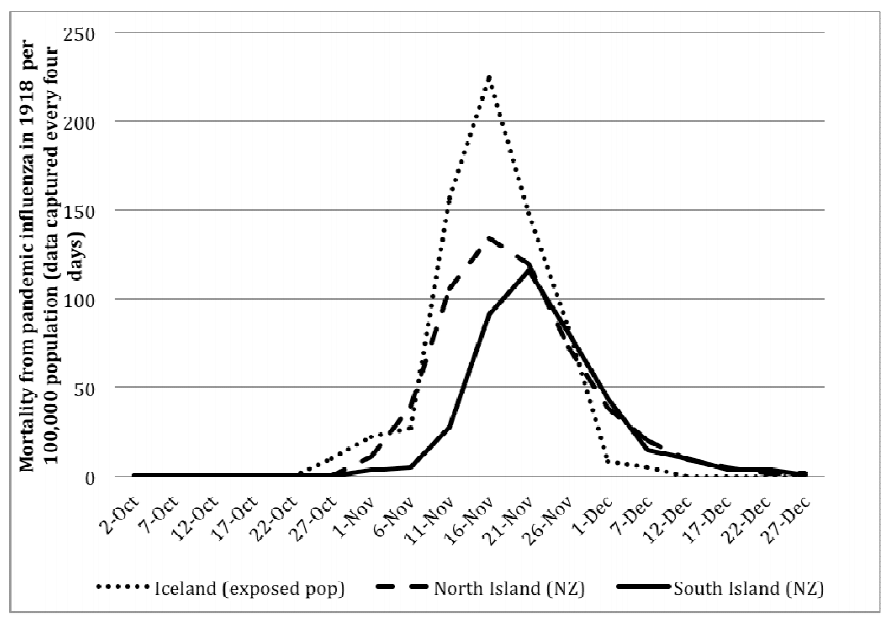

A key question for business continuity is how long might an epidemic go on for? It’s been a long time since we’ve seen a nation-wide epidemic from such a deadly form of influenza. While this virus is different to the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918, and medical practice is greatly improved there may be some opportunities to learn from that epidemic. Several characteristics in New Zealand were:

- the disease had a short incubation period of around 48 hours

- the epidemic came in waves. The first wave was in July 2018, but the second, November wave was more lethal

- it took around a month from the return of troopships from the Great War in late October 1918 to the second wave peaking in New Zealand

- it reached epidemic proportions from late October, peaked in late November and was over by early December

- community doctors were overwhelmed and able to do little to halt the course of influenza in those affected

- around 30-50% of the New Zealand population is thought to have been ultimately infected before the disease “burned out” for lack of contact with new people to infect

Deaths from Second Wave of 1918 Spanish Flu in New Zealand and Iceland

There are some grounds for thinking that a modern epidemic would be different.

- Incubation period; the incubation period for COVID-19 appears to be longer, although there is evidence that people can be infectious during the incubation period or may be asymptomatic – unaware that they have the disease and likely spreading it.

- Medical practice: medical knowledge and practice is much improved over the last century. Little was known in 1918 about the cause of the disease or how it spread. Some ineffective treatments might have helped the infection to spread. Community doctors were overwhelmed, able to do little to halt the course of influenza in those infected. With no effective treatment, many people died from secondary infections.

Should the virus take hold in New Zealand, a key goal of public health officials will be to slow the spread so that the health system isn’t overwhelmed. Assuming that this is at least partially effective, we might expect a slower rise and fall than occurred in 1918.

Lessons from the Diamond Princess

It’s apparent from China’s response to the virus that laboratory confirmation plays a significant role in containing the disease. The handling of the Diamond Princess in Japan illustrates what can go wrong when the isn’t enough lab capacity. Japan’s management of the Diamond Princess cruise ship quarantine has been widely criticised. However to me the Japanese health system appeared to be overwhelmed by just one cruise ship carrying just 3,711 passengers and crew.

As an example – a striking aspect of the quarantine aboard the Diamond Princess was the very low daily rate of diagnostic testing. The vessel carried 2,666 passengers and 1,045 crew when it docked at Yokohama on 4 February. However the Japanese medical authorities could only test 300 people each day.

I’ve travelled to Japan and expect I will do so again – it’s fascinating mix of ultra-modern, conservative and exotic. However it’s also surprising to find such an apparently low state of diagnostic capability in a modern country with close travel connections with China and time to prepare. As of Feb 12, after the ship had been quarantined for 7 days, just 492 samples had been tested. In addition there appear to have been logistical difficulties with sampling on board the ship. While the focus of reportage was on quarantining passengers from each other, it turned out that the disease was prevalent amongst the crew. Meanwhile the crew were all eating together in a common mess hall on the ship. This illustrates how it’s vital to address all sources of contagion, customers and crew alike.

It is good to hear that New Zealand has three laboratories which can test for the virus. I hope that the authorities are taking advantage of this time to ramp up the capacity of those labs.

What an epidemic may look like from a business perspective

At Navigatus we’re planning for a scenario where there are local epidemics of 8-12 weeks duration, possibly in several waves. Under this scenario the virus becomes part of the background with no special controls by the southern hemisphere summer in late 2020.

5. How would that affect us? (Business Continuity Risk Evaluation)

Key tools in this phase will be:

- social distancing – e.g. cancellation of sporting events, concerts and other social events that encourage large groups of people to mingle in close contact

- closure of schools and other learning institutions in Japan

- lockdowns – in Italy with movement strictly controlled and enforced by local government, health officials, the police and military

- telephone triage – in Japan to reduce loads on hospitals, encouraging most people to stay at home and look after themselves

- community based assessment centres – when hospitals are overloaded

For any enterprise a key business continuity issue is the possibility of workplace access restrictions. For us it won’t much matter whether those risk treatments are mandated or simply recommended. Our work-from-home trial demonstrates that our pandemic response plan works while maintaining client service. So we’ll probably be one of the early organisations to start working from home, because we can, and possibly one of the later ones to return.

6. What can we do? (Business Continuity Risk Treatment)

Our business continuity risk treatment is for all employees to work from home. We’ve been working towards this for several years – for any event that prevents us from working in our offices. Computer access has previously been an issue, but we recently completed a programme of moving all staff onto laptops with remote access to our servers and to our cloud services.

While some parties are planning for a graduated response, there may be little or no warning. Public health officials fear an “iceberg” of infections – where the virus circulates unseen in the community for weeks before a few cases come to the attention of public health officials. Over the course of several days the situation rapidly moves from laboratory confirmation of a first case, to tracing local contacts, to realising that the trail has gone cold without an external source, to recognition that there must be a reservoir of disease already in the locality. In Italy the public messaging changed from “we’ve got this under control” to “communities under lockdown” over a matter of hours. For these reasons we encourage our staff to take their laptops home every night.

We’re also monitoring the situation daily and discuss the plan with all staff in our weekly team meetings.

7. What have we learned? (Monitoring and Review)

Pandemic Business Continuity Planning

We haven’t needed to put the business continuity plan into action yet, but we have tested all staff working from home. That went fairly smoothly on the day, including video conference calls. We also found that testing this aspect of the plan was a great way to communicate with staff and helped raise awareness with our customers and suppliers.

To know what it’s like when an epidemic strikes please see the insightful post by my colleague Geraint Bermingham, reflecting on personal lessons learned during the SARS pandemic.

The next step is to discuss with our customers what their pandemic plans are, so that we can interface with them as seamlessly as possible. We’ve already started some of those conversations. In the meantime we’ll continue to review our business continuity plan as we learn more.

About the Author – Kevin Oldham

Kevin Oldham is a director of Navigatus with a depth of experience in helping clients to achieve success in an uncertain context. A brief profile for Kevin can be found here.

Comments (4)

Good article Kevin. I travel to work using 3 modes of public transport (Bus, Ferry and Train) each day, and at this time of year the downtown Ferry Building is packed full of cruise ship passengers from overseas doing day trips. This morning I drove to work and I am making full use of hand sanitizer available in our office. That's my current plan - its not good for my carbon footprint but I think public transport is a petri-dish.

That's an understandable response. It's also affecting how I think about social distancing despite no local transmission as yet.

Nice use of the risk management model, and useful background of the 1918 pandemic to put things in a local context - it worked! I've got a plan to work from home.

[…] government wants a repeat of Japan’s Diamond Princess saga on its doorstep. I expect it will be a new requirement that cruise ships have expanded and better […]